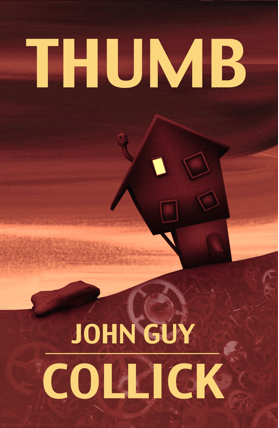

John Guy Collick’s novel, Thumb, takes place on what its characters literally consider the body of God. More specifically on, “A flat singularity (carrying) the unfinished body of God through an empty universe.”

John Guy Collick’s novel, Thumb, takes place on what its characters literally consider the body of God. More specifically on, “A flat singularity (carrying) the unfinished body of God through an empty universe.”

The inhabitants of Collick’s universe not only live on this colossal body of God, they are also its architects and builders. The title, Thumb, refers to God’s thumb and is a physical location much like a mountain or a river. For my part, I believe it is one of the most unusual worlds I’ve ever run across. Moreover, as November is Sci-fi month, I wrote to Mr. Collick and asked if he’d be willing to write a guest post based on a couple of questions I posed.

Lucky me—lucky you—he graciously agreed. Here then, are his answers…

What inspired you to write your novel, Thumb; and what sources, if any, influenced your creation?

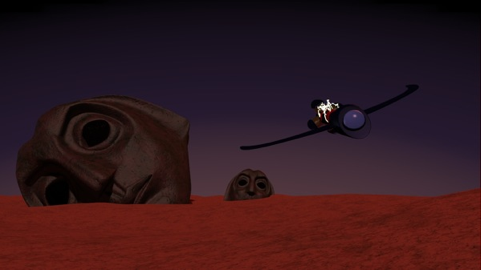

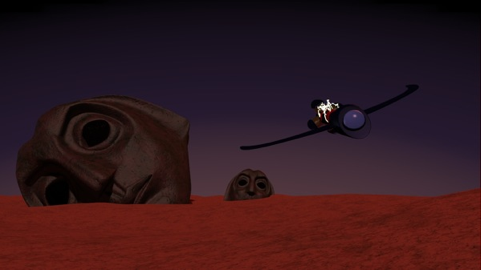

John Guy Collick: The idea for Thumb came to me in a dream many, many years ago. I saw a colossal mannequin lying on its back in the desert, and a man in blue robes standing in front. Millions of people had been making this giant puppet for hundreds of years, the plan was that it would come to life and save them from a dreadful catastrophe. As time went by they forgot the original purpose and ended up in-fighting amongst themselves – Head against Hand, Heart against Shoulder etc. Every time I revisited the idea the body got bigger until, in Thumb, it stretches half a million miles from head to toe, and floats on a flat singularity at the end of the universe, when all the suns and planets are dead.

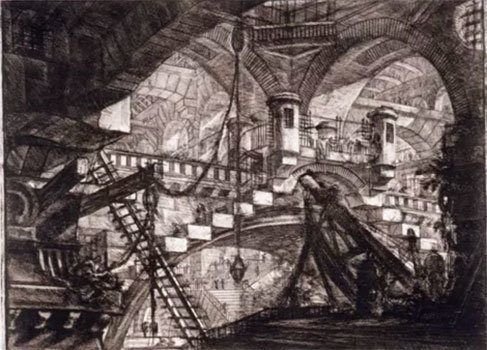

The basic premise is that all the remaining sentient races in the cosmos are being carried to the next universe by their gods. For whatever reason, humanity has no gods left and is therefore frantically building their own immense Frankenstein’s monster from fragments brought out of the past. Once it’s complete it will come to life and carry the last few people into the new universe. There is a strong Gothic theme to the series. The Gothic novels of 18th-century writers like Ann Radcliffe introduced the idea of an unknowable cosmos littered with immense fragments of the past. The wonderful Carceri (Prisons) of Giovanni Battista Piranesi capture this perfectly. When I’m describing the interior of the body of God in the sequel to Thumb, Ragged Claws, I draw heavily on his imagery.

I’ve also always been a big fan of early 20th century absurdist and fantastical writing, particularly authors like Franz Kafka and Mervyn Peake (in fact the city of Metacarpi is based on Kafka’s Prague).The idea behind the universe is fundamentally surreal. Like the characters in Kafka’s books, the people in Thumb live in a universe without logic marked by infinite landscapes and layers upon layers of mystery, but very few of them ever question the essential strangeness of their situation. Interestingly, a couple of readers initially assumed that I’d written a religious novel, which is not the case. None of the humans at the end of time worship the God or are in any way religious, it’s just a being they’ve been told they have to make in order to survive.

Modernist writing can be difficult and obscure, especially when the author emphasizes the surreal nature of their story through the language itself. I wanted to write about a Kafka-esque universe, but in the form of a straightforward high-octane adventure novel, I like to think of it as Kafka meets Indiana Jones. I’m also a huge fan of British New Wave Science Fiction, especially the baroque fantasies of Michael Moorcock and the urban wildernesses of J. G. Ballard. The universe of Thumb, with its infinite spaces of concrete, rusted machinery, iron, and dust, owes a lot to Ballard’s disaster novels – especially The Drought (1964) and The Terminal Beach (1964). In the latter is a short story called ‘The Drowned Giant’ in which an immense corpse is washed up on a beach, and just treated as an interesting curio by the locals before it decays into nothing. No-one questions why it’s there or where it’s come from, its presence is accepted, in the same way, that very few people actually wonder about the God they are building in Thumb. Ballard’s stories took their imagery from British urban landscapes in the 1960s and 1970s, where I grew up – post-boom concrete jungles littered with decay set between un-reconstructed bomb sites from the Second World War. I’ve tried to retain a Modernist/Expressionist vibe in the artwork I’m creating for the book.

As an avid science fiction reader, what science fiction or fantasy worlds stand out in your memory as exceptionally unique?

John Guy Collick: The two fantasy landscapes from novels that have stayed with me more than any others are the world of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast Trilogy, and the future Earth of William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land.

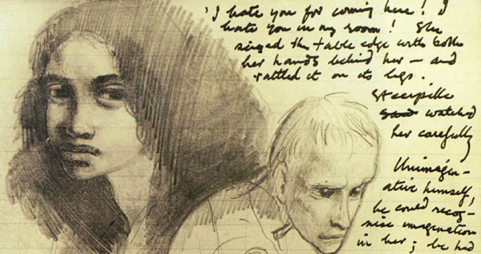

The Gormenghast Trilogy stands out as one of the most peculiar set of novels ever written in the UK. Mervyn Peake was a war artist who started writing the first book, Titus Groan, as therapy following a nervous breakdown. In the stories, a set of outrageously grotesque characters live in the vast sprawling castle of Gormenghast, an infinite chaotic mass that combines just about every conceivable architectural style. The day to day routine of the inhabitants is bound by ancient and meaningless ritual which dictates their every waking moment. There’s very little plot in the first novel – by the end the eponymous hero, Titus, is still an infant – but the evocation of this insanely baroque world is stunning. Peake describes both architecture and people by layering description on description, exaggerating details to the point where they virtually take on a life of their own. It’s like reading Dickens on Acid. In typically grotesque fashion people are often described as if they were things, and objects take on the characteristics of people.

The second book, Gormenghast, is slightly more conventional (only just) in that it describes the rise of evil within the castle in the form of the renegade servant Steerpike. By the time Peake wrote the third book, Titus Alone, he was already suffering from the illness that would eventually claim his life. It’s very sketchy, really more of an outline than a book, but it still captures an utterly strange universe filled with exaggerated characters and meaningless landscapes. Peake was one of the first war artists to enter the concentration camps towards the end of World War Two and the overwhelming image in the book is of a world populated by dispossessed wanderers lost in the shadow of an impersonal factory of evil. Michael Moorcock was also immensely influenced by Peake, directly in his two novels The Golden Barge (1958) and Gloriana or the Unfulfill’d Queen (1978).

The bulk of William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land is set in the distant future when the sun has died and the Earth is locked in perpetual night. The last remnants of humanity huddle in a pyramid fortress called the Great Redoubt, while all around them gather strange monsters and beings, most of whom seek to destroy man. The novel tells of the hero’s quest to rescue the lone survivor of the Lesser Redoubt which has been overwhelmed by the creatures of the wilderness, and so he has to journey through a landscape built straight out of a nightmare. Sadly the book is virtually unreadable because Hodgson chose to write it in the style of a 17th-century religious tract, and so the language is very archaic, repetitive and overblown. If you stick with it, however, he builds up a wonderfully creepy world populated with sinister, incomprehensible entities. Most of these are merely hinted at – the Country of the Great Laughter, the Thing that Nods, giants glimpsed in clouds of light or engaged in unknown tasks by immense red pits and kilns. Surrounding the Great Redoubt are the Great Watchers, beings that have slowly approached the fortress over centuries and now sit and stare at it with an obviously malignant intent that is never fully explained. The Night Land stands out as a forgotten classic of Science Fantasy, and if you can wade through the turgid prose and glacial pace it leaves you with images that can haunt you for years.

I’ve just finished the first draft of the second book in the series, Ragged Claws, and I’m hoping to release it early next year. At the moment the plan is for four novels in total. The third is called Antihelix – the title for the fourth is, as yet, undecided.

I can hardly wait for the release of Ragged Claws. If you haven’t read Thumb–do so! Also, if you enjoyed this post, you can read more by the author at: John Guy Collick, on and on I sped into futurity…

Purchase Thumb at the following links:

Amazon US Amazon UK Smashwords Paperback

Once again, John Collick reminds us of books read many years ago and completely forgotten about since, and persuades us we really have to read them again. The world of Thumb is no less intriguing that the world of The Night Land, and John has done wonderful job in his visual creation. The Carceri series is spot on for the interior of the Colossus. Ragged Claws promises to be a book worth waiting for. Hope it won’t be too long though.

I couldn’t agree with you more, Jane. I love reading John’s blog just to see what treasures he uncovers for us.